Skip to Chapter: 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12

CHAPTER 1

The 100th anniversary of the Yale Aero Club is still two years away, but the 50th anniversary of the modern day Yale Aviation is this coming fall. So, in view of that (lesser) milestone, I would like to share my recollections and memorabilia of the first two or three years of Yale Aviation. This will not be a history of Yale Aviation, per se, but Yale Aviation history, and I have titled it as such.

I was a sophomore in the fall of 1964 when three individuals proposed forming an organization focused on flight training and proficiency. It wasn't going to be a social club. I jumped on board immediately. Looking back, I know I didn't have the passion for aviation that consumes me now, but I spent my summers in Branford, Connecticut, and I remember watching every plane or helicopter that flew by. At Yale in 1964 I was a sportswriter for the Yale Daily News, but aviation became my beat, and I like to think that I helped the fledgling organization get the publicity it needed.

I was a sophomore in the fall of 1964 when three individuals proposed forming an organization focused on flight training and proficiency. It wasn't going to be a social club. I jumped on board immediately. Looking back, I know I didn't have the passion for aviation that consumes me now, but I spent my summers in Branford, Connecticut, and I remember watching every plane or helicopter that flew by. At Yale in 1964 I was a sportswriter for the Yale Daily News, but aviation became my beat, and I like to think that I helped the fledgling organization get the publicity it needed.

Appended to this brief introduction is my first article about Yale Aviation for the Yale Daily News which was published on October 16th, 1964. Over the course of the next several months I am going to submit to your editor additional news stories, photographs, and remembrances. Some of the material will be short, some lengthy. There will be lots of facts, and if you permit me, some opinions. I'll report this slice of history as best I can, but remember that these observances are mine, and I'll take full responsibility for reporting what I saw. I invite your comments. My email address is: travelair@centurytel.net

I've been active in aviation for almost fifty years. I'm kind of hoping that next year I will get the FAA's Master Pilot Award which goes to an aviator with fifty years of experience and no reported accidents. (The "no reported accidents" issue might be a problem, but I don't think the FAA knows about two incidents with a Pitts and one with a Super Cub.) Commercial, single and multiengine land, instrument, and commercial rotorcraft. 5200 flight hours. Charter pilot, fire patrol pilot, commercial helicopter operator. Owned two airplanes before I owned my first car. (Which puts me in the good company of John Travolta who owned an Ercoupe before he owned a car!) Naval air intelligence officer (which more than a few people have told me is an oxymoron). Built

I've been active in aviation for almost fifty years. I'm kind of hoping that next year I will get the FAA's Master Pilot Award which goes to an aviator with fifty years of experience and no reported accidents. (The "no reported accidents" issue might be a problem, but I don't think the FAA knows about two incidents with a Pitts and one with a Super Cub.) Commercial, single and multiengine land, instrument, and commercial rotorcraft. 5200 flight hours. Charter pilot, fire patrol pilot, commercial helicopter operator. Owned two airplanes before I owned my first car. (Which puts me in the good company of John Travolta who owned an Ercoupe before he owned a car!) Naval air intelligence officer (which more than a few people have told me is an oxymoron). Built  Pitts Special while I was in the Navy. Farmer in Kalispell, Montana, for the last 40-plus years. Last 25 years just a round-dial, leather helmet kind of pilot. Currently have four airplanes: 1928 Travel Air 6000 (same model Delta Airlines started passenger service with in 1929), 1948 Bucker Jungmann (biplane used as a trainer by the Germans and Japanese in WWII), homebuilt Super Cub, and a home built Bucker Jungmeister (developed by the Germans from the Jungmann for the 1936 Olympics in Berlin when aerobatics was an Olympic event).

Pitts Special while I was in the Navy. Farmer in Kalispell, Montana, for the last 40-plus years. Last 25 years just a round-dial, leather helmet kind of pilot. Currently have four airplanes: 1928 Travel Air 6000 (same model Delta Airlines started passenger service with in 1929), 1948 Bucker Jungmann (biplane used as a trainer by the Germans and Japanese in WWII), homebuilt Super Cub, and a home built Bucker Jungmeister (developed by the Germans from the Jungmann for the 1936 Olympics in Berlin when aerobatics was an Olympic event).

CHAPTER 2

Writing profiles of the three individuals who founded Yale Aviation fifty years ago has been an inspiring experience. None of what follows was written when I actually knew these people. It comes directly from my brain now; however, the visual images are unadulterated by time. I can see and hear people talk. Flights come back to me like a GoPro CD. Maybe I can’t remember the takeoff, but I can remember the countryside we flew over, the runway we landed on, and even the temperature on the ramp. Is aviation like that for you? It should follow that I’d have been a good student, but, alas, that wasn’t the case.

I call myself a “Type C” person, beyond a “B.” I’ve met “Type A” aviators and I stay away from them. One should approach aviation with due deliberation but also infuse the joy that comes with every flight. I’ve flown a B-17, a Ford Tri Motor, a jet or two (okay, two), even a Travel Air biplane on floats, and most of my friends own more than one airplane. One of them owns dozens. Like Marcel Proust whose reveries flooded him whenever he ate a small cake, I smell avgas and my mind reels with aviation happenings. I can remember the new smell of 6405W, Yale Aviation’s first Cherokee 140. Oh gosh, you are getting a stream of aviation consciousness, and I digress.

In 2025 I will have been flying for half the history of powered flight. I’ll be 80 years old. That’s a reasonable goal. (A friend of mine just retired from corporate flying at age 80. He let his sim quals run out.)

When I was in college I spent rainy days at the Sterling Memorial Library high up in the stacks where the aviation collection was kept. There were hundreds of documents, and I think I looked at every single one. I discovered “Slats” Rodgers and “Old Soggy No. 1.” I read a World War I flight manual and taught myself aerobatics. I also frequented the periodicals reading room where I kept picking up the monthly publication of the military airlift command and the weekly magazine Aviation Week and Space Technology. I still subscribe to the latter and I recommend it. In short, I have studied aviation, and I can honestly say that I would rather read about the people of aviation than their hardware. So, I promised you profiles of the three founders of Yale Aviation in 1964; let’s get on with it.

Frederick W. Smith, Class of 1966, was already an accomplished pilot when he came to Yale. I probably met him four times. Yale Aviation was not a social club. Members could pass each other in the office of New Haven Airways and not know that they belonged to the same organization. Fred had a twin-engine airplane from time to time, and I flew with him once in a Twin Comanche on a photo flight over the campus. I distinctly remember that the door (which was on my side of the airplane) was secured with a screwdriver through the latching mechanism. Fred was not concerned.

As the world knows, Fred founded Federal Express, creating a new industry. It wouldn’t surprise me at all if it is a case study at the Harvard Business School. I can’t begin to write the history of FedEx in a paragraph or two, but I feel quite comfortable describing Fred as both a visionary and a pioneer. That puts him in the august company of the Wright brothers, Billy Mitchell, and Juan Trippe. Lindbergh was a pioneer but not a visionary, so you can see that a great many famous aviators do not make the cut.

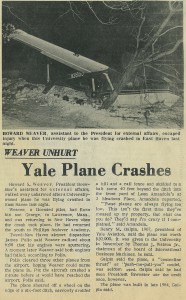

Our second founder was Howard S. Weaver, Class of 1948. Mr. Weaver had an office in Woodbridge Hall where he worked as an assistant to President Kingman Brewster. He had various official titles, he knew everybody, he could arrange things, and he could get things done. I’ve always thought that if there were any bodies buried during the Brewster administration, Howard Weaver would have known where and how deep.

Mr. Weaver flew B-25s in the China-Burma Theatre during World War II. There was a rumor that his civilian pilot’s license was for multiengine only. Mr. Weaver’s office drew up the incorporation papers for Yale Aviation, and the organization was run from his office. As Yale Aviation’s second president (after Fred Smith) I was called in from time to time to sign something. I suspect that Fred’s experience was similar to mine. If it seems strange that a campus organization could be operated under the nose of the Yale president, it should be noted that Kingman Brewster was a Navy patrol plane pilot in World War II and had an abiding interest in aviation.

If Howard Weaver was the corporate “suit,” and Fred Smith was the undergraduate and future visionary, can we describe Professor Norwood Russell Hanson in a phrase or two? The answer is no; not remotely possible. I would like to call him a friend of mine. We flew places together, and he borrowed my airplane many times. I should have tried to coax some aviation stories out of him; I heard a few, but most of them came later, from other people. He was an academic and an aviator, and I only knew him as the latter. We shared the passion: while mine was nascent, his was full-blown, virulent, and contagious.

Born in 1924, Russ Hanson soloed in 1940 at the age of 16, and by the age of 19 he was a Marine fighter pilot flying off the carrier Franklin, closing in on Japan in the last year or two of World War II. He had 2500+ hours, mostly in Corsairs. Hanson told me that after one sortie he came back to the carrier and it wasn’t there, so he landed on another carrier. The deck was so full the crew pushed his airplane over the side. At one time he was assigned as a test pilot for a facility that repaired Navy fighter planes. It must have been in the San Francisco Bay area, because he got into trouble for looping the Golden Gate Bridge. He also told me that the test flying was mostly boring, so he buzzed a nearby Air Force base inverted. Trouble was he flew under a bomber that was landing and they read his numbers off the bottom of his airplane!

After the war Hanson earned degrees from Chicago, Columbia, Oxford, and Cambridge. He was a concert-class musician, rode a huge Harley, and had a disassembled Jaguar SS100 in his basement. His specialty was the philosophy of science, and if you google his name today you will find all kinds of incomprehensible stuff, but you won’t find what I’m going to tell you about right here. There were whisperings that he was lured to Yale with a $40,000 a year salary (which you can reasonably multiply by ten or more to get the equivalent dollars today. Tuition, room, and board was $2500 in the mid-1960s).

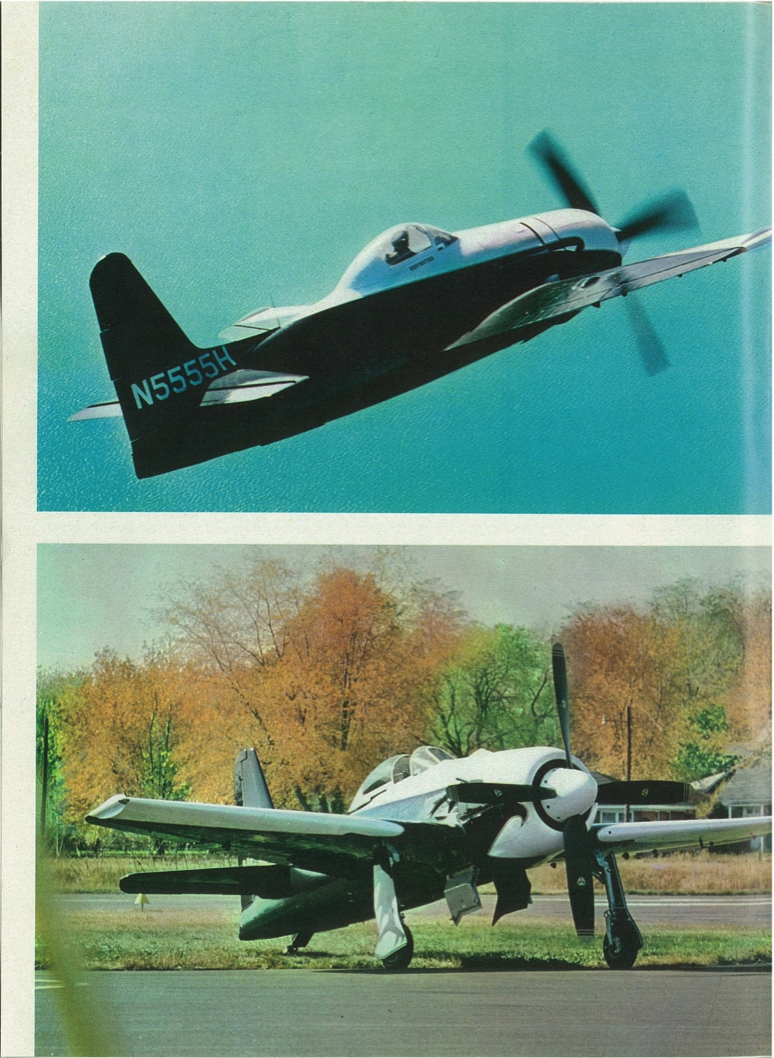

Beyond all the academic accolades Professor Hanson owned and flew a Grumman F8F-2 Bearcat, the fastest prop-driven fighter ever built. He delighted in buzzing the Yale Bowl during football games. It sounded like rolling thunder, and the hair on my arms still stands on end. Of course he got into trouble for this too. Professor Hanson felt that the Bearcat was the epitome of industrial art and when well-flown (by him, naturally), it was educational, and we should applaud his efforts on our behalf. I thought it was great! He had a streak of arrogance, but he wore it perfectly. Personally, I found him extraordinarily polite and humble. I guess he had a dual persona, and I only knew one of them.

I first became acquainted with the professor when his airplane caught fire at the New Haven airport. He was cranking the engine and raw gas was streaming down the sides of the airplane. When the engine fired the flames reached all the way to the tail. Hanson closed the canopy and kept cranking. The engine started fitfully and blew the fire out. Fire trucks came and there was a lot of excitement, but Russ behaved like this was no big deal; it happened quite frequently.

You don’t have to be much younger than me to have never seen a Bearcat fly, so I am going to describe what the hangar rats saw when Professor Hanson came to the airport to fly his airplane. Hanson would start up the Bearcat, usually without the histrionics of fire engulfing the airplane. With the engine barking and popping, he’d taxi deliberately to the first intersection on runway 19 (it was 19 at New Haven in those days), backtaxi to the very end, and swing around facing south. Set the power well above idle, and just sit there. He basically “took” the runway and nobody challenged him for it. Hanson told me once that the engine could easily drag the airplane with the brakes locked, so the power was usually set just below that threshold. He seemed to sit there interminably, but eventually everything must have been satisfactory because the brakes were released and the power came up quickly and smoothly. Today, fifty years later, I can see every movement like it was burned into my memory. The sound was magnificent! It swelled and assaulted the ears. I can’t imagine that anyone on or near the airport was not watching. Off the ground in 3-400 feet, maybe less. Gear up. Nose pushing over. I’d like to say the huge prop cleared the runway by no more than two feet all the way to the end, but it was probably more like four or five. By the end of the runway the plane was level and going really FAST. Pull to a forty-five degree angle, very short delay, and then left aileron rolls until the plane was out of sight, only a black smudge of cremated fuel marking its path. WOW! “The essence of exhilaration!” Russ would have said in his clipped British accent.

Of course everybody who watched that performance knew he’d be coming back pretty soon. A couple of whifferdills, an octoflugeron or two, and all workaday groundbound cares are erased. Not to mention the prodigious amount of fuel the ‘Cat could use up when flown the way Russ liked to fly. A black pinprick in the distance, gear down, a graceful nose-high arc to a carrier-style kerplunk on the numbers. Roll out, almost no brakes, taxi to the hardstand, bring it up to 1200 rpm for thirty seconds to scavenge the oil, idle-cut-off, prop spins to a stop. Now you can breathe normally again!

We’ll learn a lot more about Professor Hanson in Chapters Five, Six, Seven, and Eleven.

Four documents are appended to this chapter:

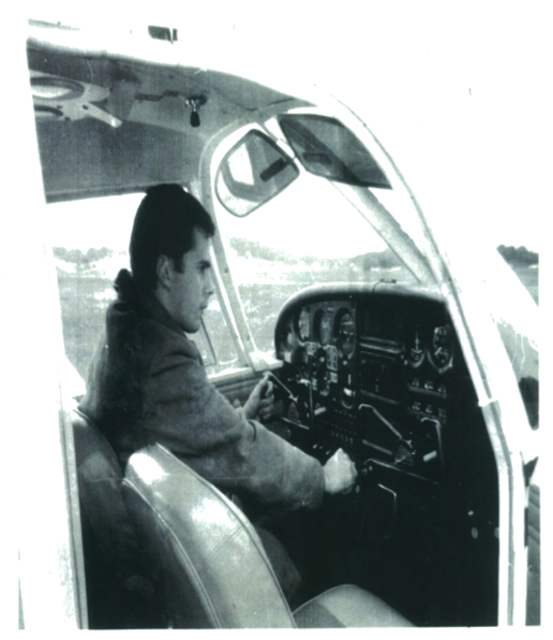

- A photo of Fred Smith in Yale Aviation’s brand new Piper Cherokee 140, N6405W. This photo was probably taken by Alexander “Sandy” Trevor, Class of 1967, who was among the first students to join Yale Aviation.

- A photo of Fred Smith in Yale Aviation’s brand new Piper Cherokee 140 written by Professor Hanson for the February 1964 issue of Flying magazine.

- Yale Aviation’s first brochure. Take note that the cost per hour in the 140 was $8.50!

- Professor Hanson’s airshow brochure.Brochure 1 | Brochure 2

CHAPTER 3

New Soloists Congratulated

Under the headline "New Soloists Congratulated" this photo was published in the March 18, 1965 issue of the Yale Daily News. The caption: Members of Yale Aviation who have soloed since November include (l. to r.) Douglas F. Schofield, 1967; Nicholas F. Kaiser, 1967; Alexander B. Trevor, 1967; Frederick W. Smith, 1966, president; G. Neild Mercer, graduate school; Henry M. Galpin, 1967; and Michael J. Levine, graduate school.

Under the headline "New Soloists Congratulated" this photo was published in the March 18, 1965 issue of the Yale Daily News. The caption: Members of Yale Aviation who have soloed since November include (l. to r.) Douglas F. Schofield, 1967; Nicholas F. Kaiser, 1967; Alexander B. Trevor, 1967; Frederick W. Smith, 1966, president; G. Neild Mercer, graduate school; Henry M. Galpin, 1967; and Michael J. Levine, graduate school.

A short article followed:

Yale Aviation's initial activities have been "highly successful," according to Frederick W. Smith, president of the group. Speaking last week at a meeting held to congratulate the eight student pilots who have soloed in the organization's plane, Smith stated that the activities of the first three months have surpassed the original plans. He reported that plans for the initial three months called for an enrollment of 30 and an average of 50 flying hours per month. The enrollment is currently 33, and nearly 250 hours have been flown. Treasurer Wood Lockhart, a graduate student in architecture, said that Yale Aviation is "meeting the budget and paying the bills." Unsolicited contributions from aviation-minded alumni have aided the group. The group is planning a dinner and reception for next month.

Hank's Private Checkride

The primary purpose of a checkride is for the examiner to ensure that the applicant has the skill and judgment to continue learning at that new level. I think everyone will agree that every flight should have an element of education in it; otherwise, you'll never become a better pilot as the hours pile up. In most cases a checkride is a positive experience. My private checkride was decidedly not, which is why I am going to discuss it here.

I started flying 6405W in November 1964 and soloed after about seven and a half hours, flying about twice a week. When I had 25 hours one of our members ran 05W off the runway and damaged the nose wheel strut, so I switched to a Cessna 172. By late May, 1965, with about 44 hours of flight time, I was ready for the private checkride.

The examiner was Mike Jellen at the Meriden airport. I feel certain that Mike worked nights at Pratt and Whitney because he was not happy to have to give a flight check that Friday morning. He was also a big man, so big that I knew the plane was going to behave differently, adding distance to the takeoff roll, and probably making power-off approaches come up short.

We seemed to start off OK, but the first thing he wanted was a groundspeed check after we had gone just three miles in about a minute and 40 seconds. I'd never set that kind of time on the computer before, but the arrow came up on a plausible number and Mike grunted. Then we went under the hood for some instrument time. "Get your g-- d--- hands off the controls; this plane will fly by itself!" Nobody had ever talked to me like that before, certainly not in an airplane. I should have dived back to the airport and kicked the SOB out. But I was only 19 years old, and I didn't know how to do that. (I do now, though, and wouldn't hesitate.)

Examiners probably don't behave like Mike Jellen anymore because instructors prefer to send their students to decent individuals. I met a "screamer" a few years later in my aviation career, and he was such a jerk it was almost comical. Mike did pass me that day, and the next few flights were with my brothers, a few friends, and my mom!

CHAPTER 4

I hope my few readers have found the first three chapters of Yale Aviation history fairly interesting. Chapter Four will probably set the standard for most boring, but I'm going to submit two documents for your perusal anyway. Please be kind enough to at least read my commentary.

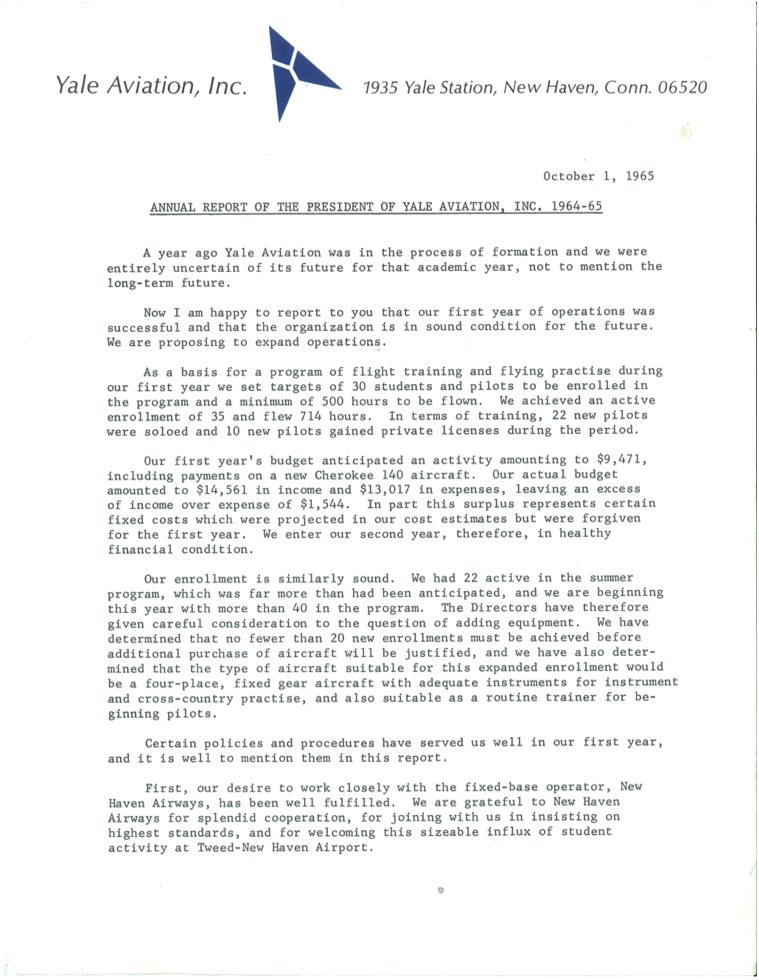

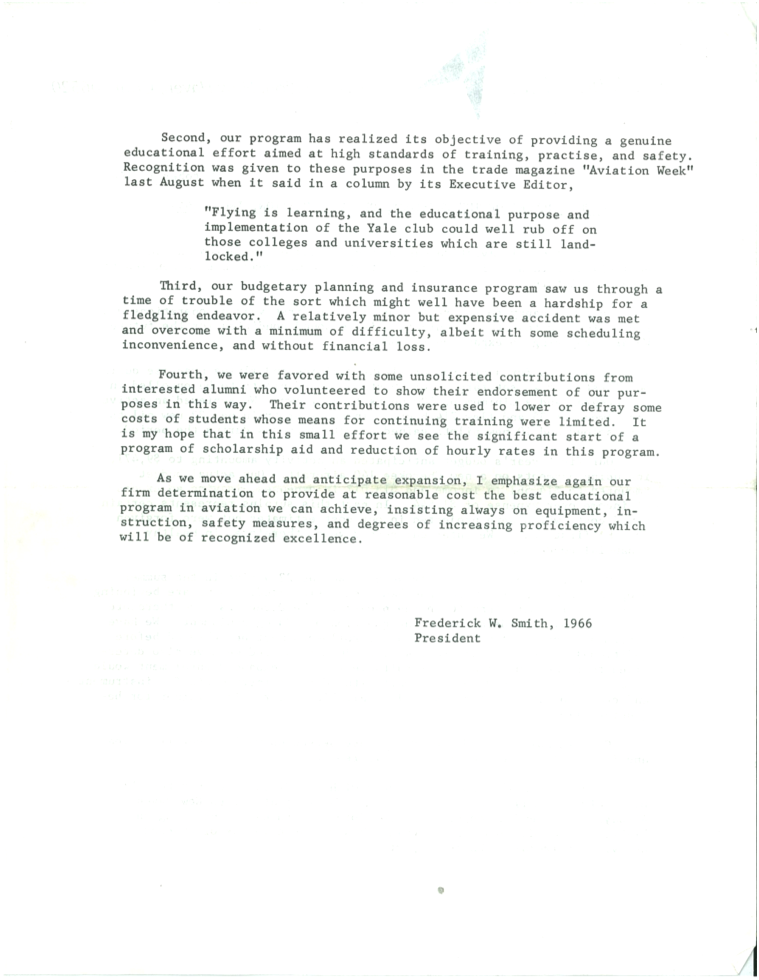

President Fred Smith's first annual report of Yale Aviation operations was sent to all members on October 1st, 1965. The organization was meeting its obligations, and the future was bright. A year later, when the second annual report came out over my signature, it read substantially the same. It was generated from Howard Weaver's office in Woodbridge Hall, and I had nothing to do with its composition. My business acumen at that time was woeful, and Fred later became a business superstar, but I can't help thinking that maybe both annual reports were written by Weaver or his very capable secretary.

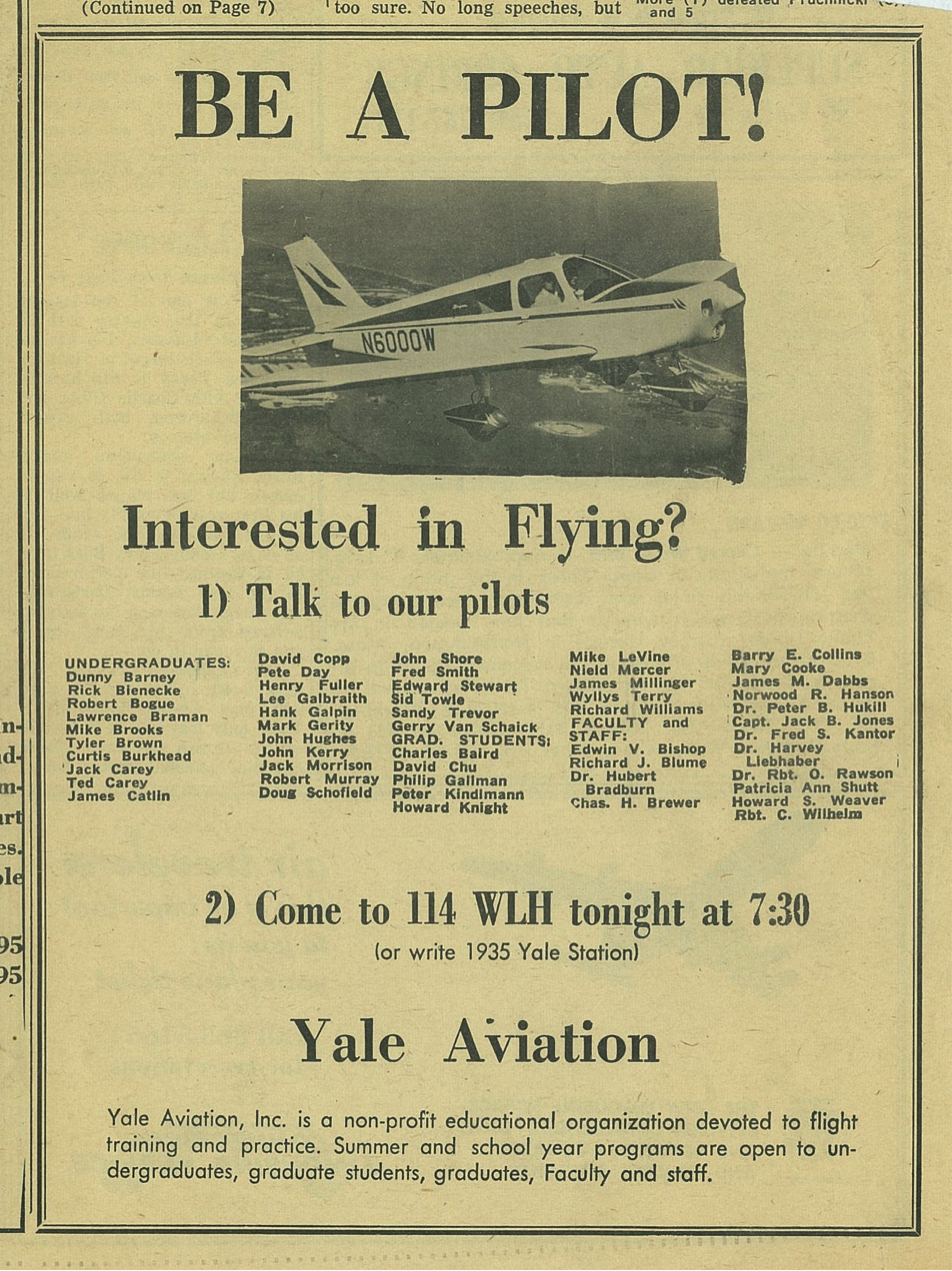

The second document is an ad that appeared in the Yale Daily News, probably in the fall of 1965. It was written by me; I don't recall if it was effective or not. Of the 27 undergraduates listed, seven were involved with Yale hockey, from Dunny Barney who was a committed fan, to Jack Morrison, who became an All-American. John Kerry was a very good hockey player who decided to concentrate on debate instead. He is now Secretary of State.

Among the list of graduate students I would like to single out Mike Levine. Fifty years ago the IBM 360 at the Computer Center ran on stacks of punch cards, and students had to reserve time on the machine. Mike Levine put Yale Aviation on the computer which facilitated our management of the organization.

CHAPTER 5

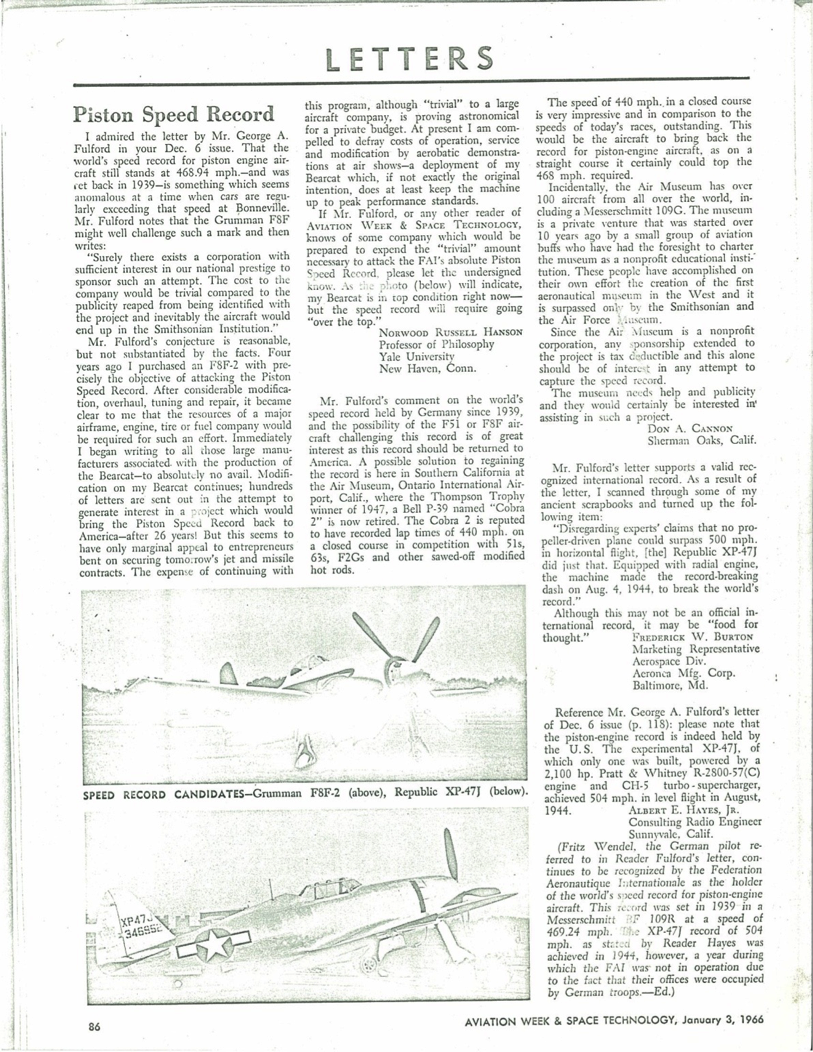

The letters page of the January 3, 1966, issue of Aviation Week & Space Technology featured a letter from Professor Norwood Russell Hanson lamenting the fact that he had been unable to drum up corporate support for an assault on the piston speed record. The official record, certified by the Federation Aeronautique Internationale (FAI), had been set in 1939 by Fritz Wendel of Germany flying a Messerschmitt BF 109R at a speed of 469.22 mph. The description of the aircraft turned out to be a bit of propaganda. The record-setting airplane was actually a BF 209V prototype which had undesirable flight characteristics. Pilot Wendel survived a crash in one of them.

Hanson's letter ignited a firestorm of interest in the piston speed record. It smoked out at least three other legitimate contenders. Other letter writers included Bruce Boland, a Lockheed Skunk Works engineer who helped virtually all of the unlimited racers at Reno, and Martin Caidin, a prolific writer of aviation books and TV series. (There is an iconic photo of Caidin's Junkers J52 with 19 skydivers clinging to the left wing. The plane slowly rolled over and dumped them all off!)

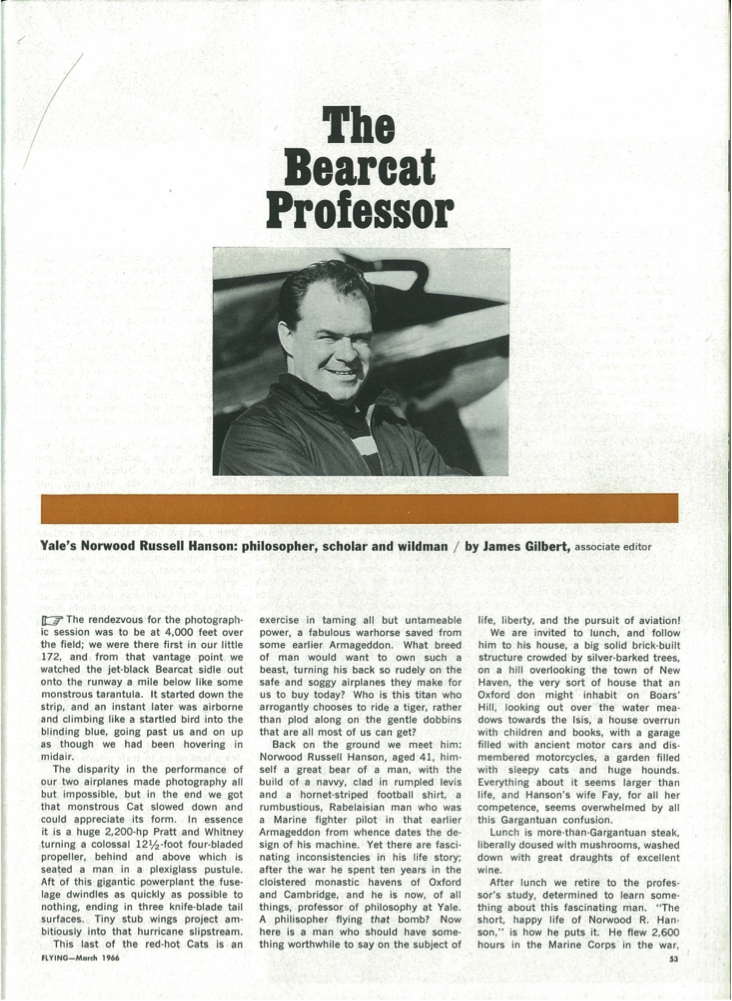

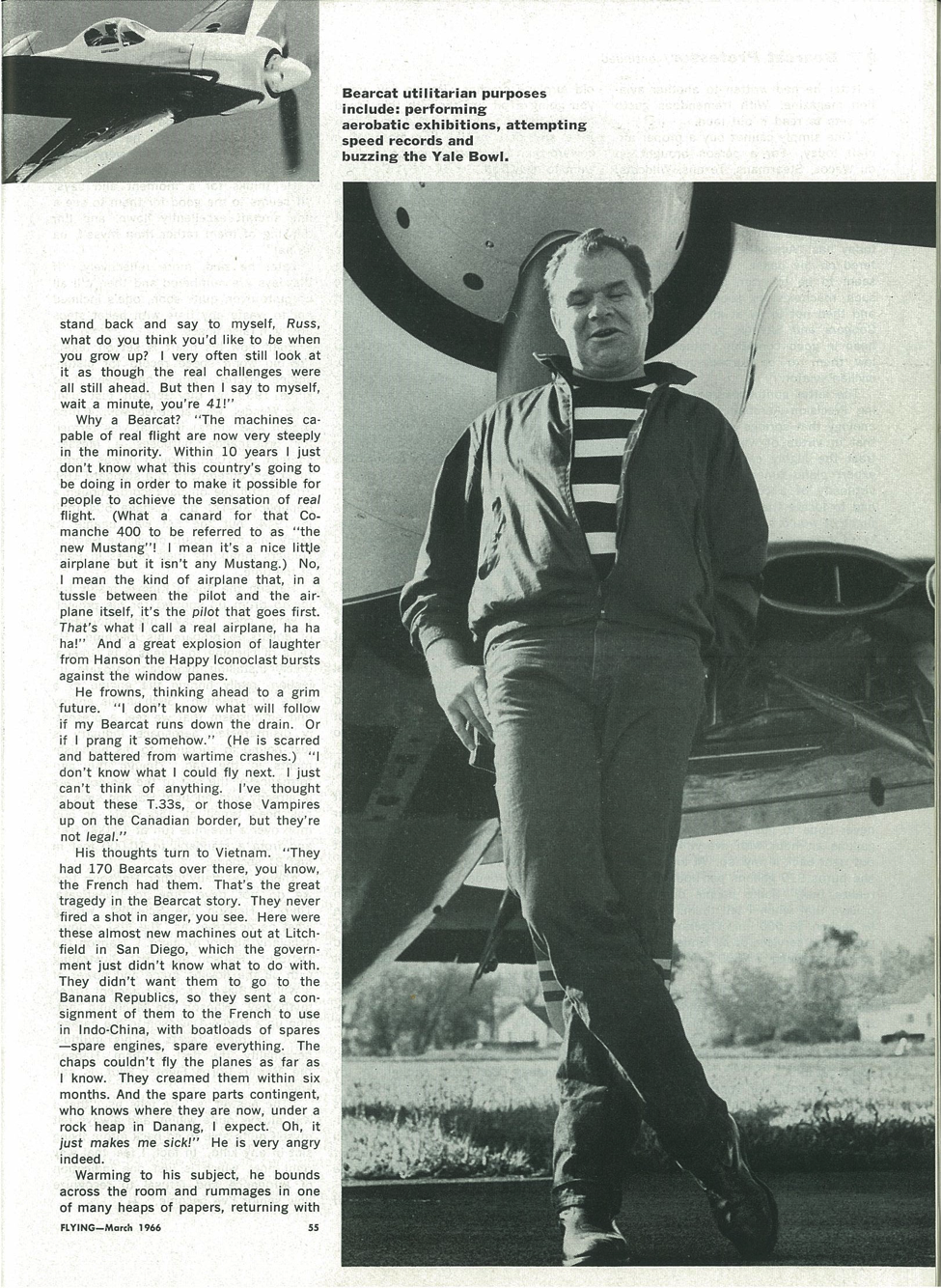

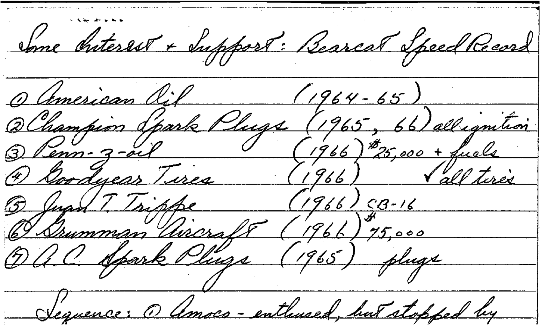

The March 1966 issue of Flying magazine had an extremely well-written article by James Gilbert titled "The Bearcat Professor." "A rumbustious, Rabelaisian man," Gilbert wrote of NRH. You'll have to look up those words yourself, but they perfectly describe the professor as I knew him.

There is no aviation journalist on the scene today who can match James Gilbert. He was an editor at Flying, at that time the most influential aviation magazine, for six years. Gilbert assisted in the classic 1969 film "Battle of Britain," flew with Neil Williams in "Aces High," and even made an appearance in "The Eagle Has Landed." (The fact that Gilbert owned and flew a Jungmeister does color my opinion of him.) It is quite fortuitous that James Gilbert was chosen, or chose himself', to write the story about Prof. Hanson.

When you read the article, pay very close attention for the italicized words. The type face makes them difficult to spot, but the emphasis perfectly reflects the way Prof. Hanson actually spoke. Enjoy!

CHAPTER 6

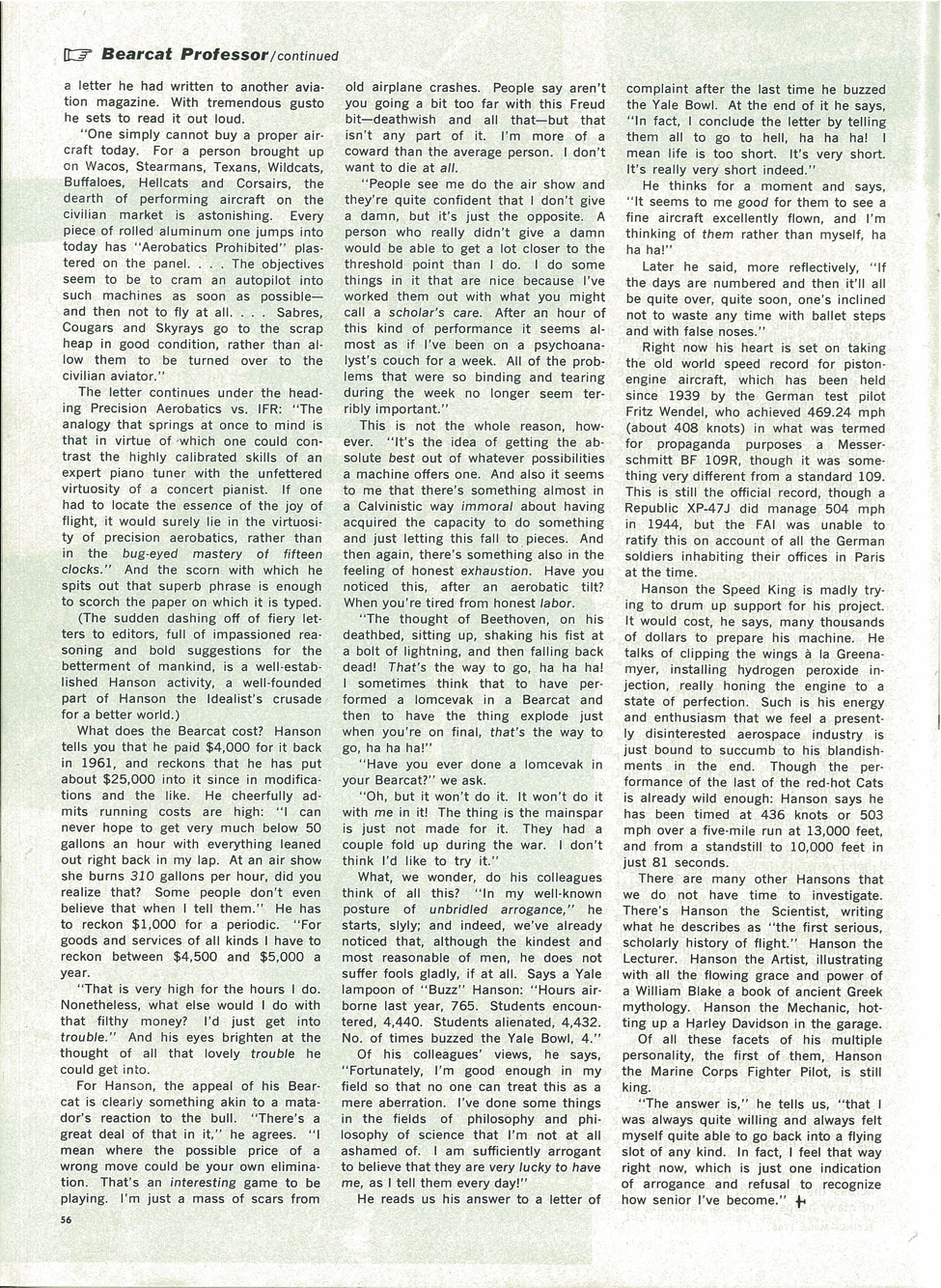

Support for Professor Hanson's speed record attempt coalesced by March, 1966, a mere two months after Hanson's letter to Aviation Week. Six major American businesses and one individual (identified only as a member of the Yale Corporation) stepped up to offer engineering services, parts, and money. We will identify all the participants next month in Chapter Seven.

On March 16, 1966, the Yale Daily News published a feature article about Professor Hanson, his Bearcat, and the impending record attempt. This article was also published in the Hartford Courant. The Courant sent me a check for $12, and I knew right then that journalism was not going to be my vocation.

CHAPTER 7

The daily news media doesn't have much interest in follow-up stories, so when I submitted some new material to the Yale Daily News later in the spring of 1966, there was evidently no interest. I still have the story, neatly typed in 30-character lines on the yellow copy paper we used in the newsroom. This is obviously the first draft, but I offer it here because it contains facts that I couldn't disclose in the "Ordeal by Flier" feature. I have also appended two sides of a 3x5 card that Professor Hanson wrote to me which puts the history of his record attempt into the most succinct form. Although he borrowed my airplane many times and we flew together to a few destinations, we rarely talked on the telephone. Most of our communications were by 3x5 cards, usually taped to the control wheel of the airplane. Here is the story:

When Hanson bought his 'Cat in 1961, the idea of taking a crack at the speed record was in the back of his mind.

While at Oak Ridge near Knoxville, Tennessee, in the summer of 1964 Professor Hanson spoke to a representative of the American Oil Company. General sponsorship of a record attempt with an unmodified aircraft was discussed.

However, the legal staff of Amoco nixed the proposal because the company had to own the plane for insurance reasons.

Hanson next sent his dossier to Champion Spark Plug and the company reacted favorably, agreeing to supply platinum spark plugs, high tension leads, and other ignition parts.

Champion has made it their policy to cover the field, however, and this was not a unique arrangement.

Then, early in January 1966 Mr. Hanson published a letter in Aviation Week & Space Technology grumbling about the lack of interest in returning the speed record to the United States.

"The competition came out of the woodwork," stated the amazed professor. A Hawker-Siddeley Sea Fury, a P-51 Mustang, and another F8F-2 Bearcat materialized as contenders.

Pennzoil contacted Mr. Hanson and expressed interest in backing the whole show with all fuel, oil, and additives and $30,000 for modifications and overhaul of the aircraft.

At the same time Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company offered to supply tires while the Allison division of General Motors was enlisted to provide technical assistance in modifications of the propeller.

Juan Trippe, president of Pan Am, Yale graduate, and member of the Yale Corporation, offered Hanson a Pratt & Whitney R-2800 CB-16 engine from a DC-6B. Mr. Trippe's generosity made this $85,000 engine available immediately, and it was on the loading platform at Miami awaiting shipping instructions.

Unfortunately, Pennzoil discovered that it had overlooked a prior commitment to Grant Weaver's Sea Fury. The oil company backed out on Weaver and felt ethically compelled to withdraw its financial backing of Hanson. Pennzoil had also, in effect, asked for a guarantee that the record would be broken, a promise Hanson could not make.

With the demise of Pennzoil, Grumman Aircraft suddenly wanted in, spurred partly by the realization that Darryl Greenamaier's Grumman Bearcat had the resources of Lockheed behind it. Grumman obviously wanted the record set under its own auspices.

After several sessions between Hanson and Grumman a tentative budget was set up, including the costs of hangar space, four mechanics, overhauling Trippe's engine, and chopping, modifying, and redesigning parts of the airframe. The budget came to $75,000, somewhat more than had been anticipated.

During this time Grumman was building up its image as a leader in the aerospace field and preparing to launch the Orbiting Astrological Observatory.

On the day that the decision was to be made whether or not to back Hanson, the OAO mission failed. Professor Hanson surmised that this failure caused a reappraisal of Grumman's public relations posture vis-à-vis the Defense Department, resulting in the Hanson 'hot rod' project being dropped. Backing the Bearcat began to look like self-aggrandizement when the aircraft company could ill afford it.

Thus Hanson's chances began to fade and he resigned himself to keeping the 'Cat as an airshow machine.

Late in May Darryl Greenamaier was clocked at about 500 mph. He retired after two passes due to severe lateral instability caused by chopping 18 inches off the rudder. Greenamaier's Bearcat utilized the CB-16 engine, clipped wings, a new canopy, and special fairings - modifications Hanson was contemplating to his own plane. Ironically Greenamaier got technical assistance from a Grumman test pilot before it was known that Lockheed was behind the project.

Hanson wrote a cryptic note on a file card: "Greenamaier will make it. FAI record still unbroken = NRH fading."

An "angel with a wad" was not forthcoming and Hanson polished his aerobatic routine. At Bridgeport last summer he delighted the crowd with screaming low passes and his patented takeoff: brakes on, Hanson would run up full power at the end of the runway. When he released the brakes the plane fishtailed from the torque but was airborne from the three-point attitude in 400 feet. Hanson sucked up the gear and leveled off, his propeller inches from scarring the tarmac. The 'Cat accelerated quickly. Climbing abruptly Hanson would bend the Bearcat into a slow roll to the left and continue his climb-out, the smoke of 2450 horses burning rich tracing the perfectly executed maneuver.

CHAPTER 8

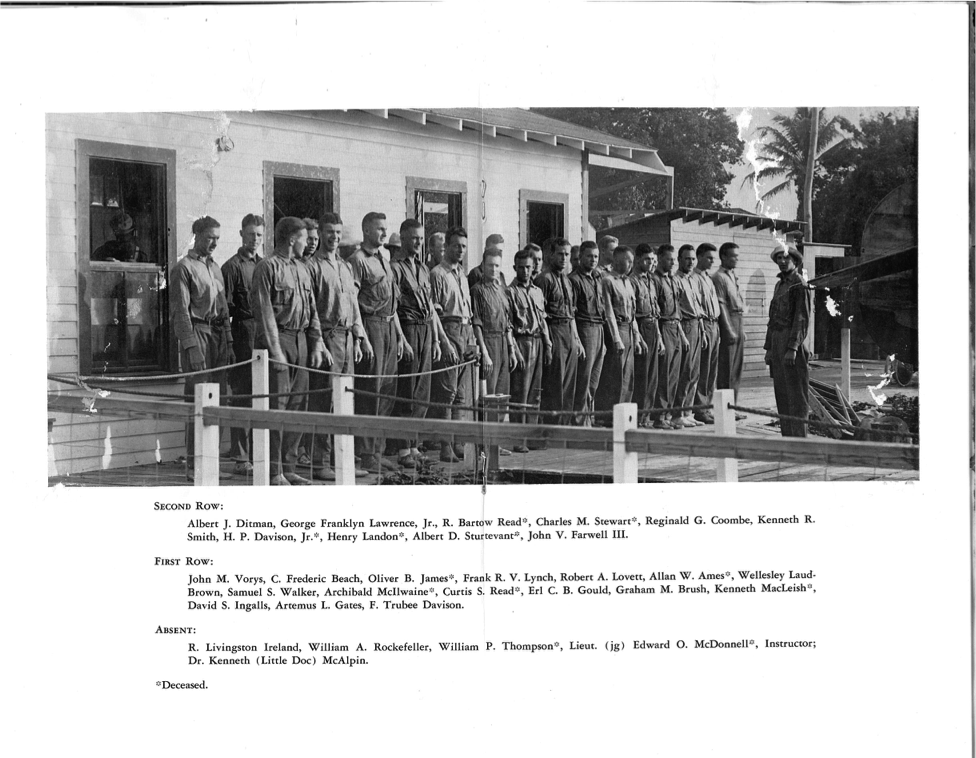

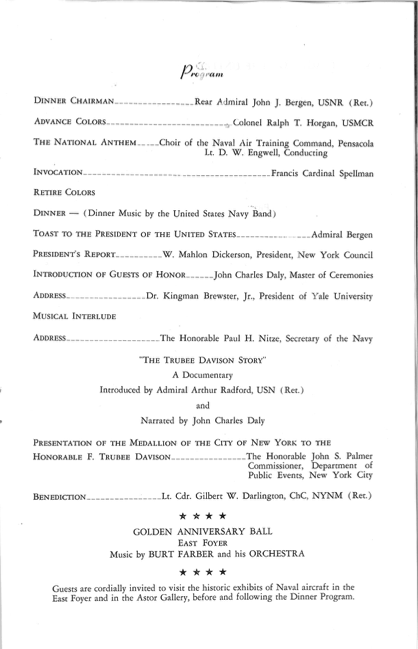

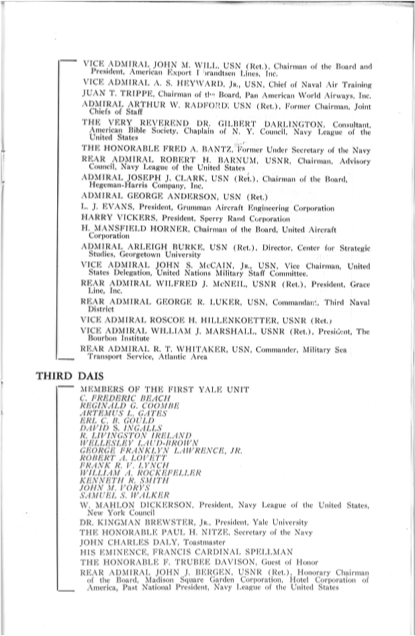

The 50th anniversary of naval aviation and the Yale Unit was celebrated on October 26th, 1966, at the Waldorf Hotel in New York City. It was an elegant affair, honoring F. Trubee Davison, Yale 1918, and his classmates - "The Aristocratic Flyboys Who Fought the Great War and Invented American Air Power." That blurb, from the cover of Marc Wortman's terrific book, "The Millionaires' Unit," is not hyperbole.

The 50th anniversary of naval aviation and the Yale Unit was celebrated on October 26th, 1966, at the Waldorf Hotel in New York City. It was an elegant affair, honoring F. Trubee Davison, Yale 1918, and his classmates - "The Aristocratic Flyboys Who Fought the Great War and Invented American Air Power." That blurb, from the cover of Marc Wortman's terrific book, "The Millionaires' Unit," is not hyperbole.

Several members of Yale Aviation attended: Howard Weaver, Doug Schofield, Duncan Bremer, Nield Mercer, Hank Galpin, and Foster Bam (Class of 1950). (More about Foster Bam in Chapter Nine.) I can't remember if we wore black tie, but it really didn't matter because our table was squirreled up on the mezzanine where we overlooked the ballroom floor and seven daises of important people.

Howard Weaver, who as I mentioned in Chapter Two seemed to know everybody, introduced us to a few admirals and generals: their plumage was awesome! I served in the Navy as an intelligence officer for about four years, and I never encountered anyone in such glittering finery.

Now, as I look back on this event, I realize that the Establishment was arrayed in front of me. Cardinal Spellman, politicians, leaders of the military-industrial complex, titans of Wall Street, and hundreds of individuals who served our country in World Wars l and ll, and won both of them! It was a privilege to be there.

Now, as I look back on this event, I realize that the Establishment was arrayed in front of me. Cardinal Spellman, politicians, leaders of the military-industrial complex, titans of Wall Street, and hundreds of individuals who served our country in World Wars l and ll, and won both of them! It was a privilege to be there.

As you page through the program, take a look at the Third Dais comprising the surviving members of the Yale Unit who were able to attend.

A couple of asides, if you will permit me. Trubee Davison was a graduate of Groton School where I also graduated. His military accomplishments were unknown at school: Groton expects its graduates to be Presidents or Secretarys of State, not warriors. And I thought David S. Ingalls was just a wealthy donor who built a beautiful hockey rink at Yale. (I spent four years as a rink rat there.) He was also the Navy's first ace!

CHAPTER 9

In November, 1966, Foster Bam, Class of 1950, gave his Citabria to Yale Aviation. Developed from the 7-series Aeroncas, the Citabria was the only airplane built in the U.S. that was certified for aerobatics. (Citabria is "airbatic" spelled backward which, at the time, I thought was pretty lame, but the name is now comfortably in the aviation lexicon.) In 1969 Mr. Bam demonstrated his Pitts Special at Yale Aviation Day, so it is apparent that he was moving up in performance when he made his generous gift.

The Citabria was not the first aircraft given to Yale. Tom Watson of IBM gave his Cessna 336 (the fixed-gear center-line-thrust twin) to the University, but it did not become an asset of Yale Aviation. We'll learn more about the 336 in Chapter Ten.

The Citabria was not the first aircraft given to Yale. Tom Watson of IBM gave his Cessna 336 (the fixed-gear center-line-thrust twin) to the University, but it did not become an asset of Yale Aviation. We'll learn more about the 336 in Chapter Ten.

Mr. Bam's Citabria had a 115-horsepower Lycoming engine. It was a good basic trainer and had to be flown very precisely to perform half decently. I had a Clipped Wing J-3 Cub in which I taught myself aerobatics from a World War I flight manual I found in the library, so Mr. Bam checked me out in the Citabria. My log book shows "immelman, slow roll, hammerhead, etc." in a 30-minute flight. I remember that it took quite a bit of arm strength to roll the plane smoothly.

My second flight in the Citabria was about a month and a half later. I felt it was my duty as President of Yale Aviation to exercise the airplane occasionally. Very few, if any, of our members had experience in tailwheel airplanes. My log book for that flight says "loops, snaps, hammerhead, emergency landing." I remember that flight like it was yesterday! I had flown east of the airport and practiced aerobatics along the shoreline. In the pivot of the hammerhead a very loud banging started, and I thought the airplane was coming apart. The banging continued as I made a long, long straight-in to runway 32. I cut the engine and quickly got out to see what had happened. The top wing fairing on the left side had come loose and punctured a lot of holes in the wing and the top of the cabin. I restarted the plane and taxied to parking with a great deal of relief that there had been no structural failure.

CHAPTER 10

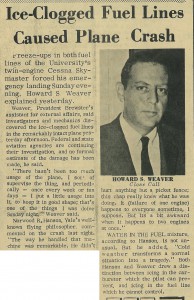

In the winter of 1966-67 (I didn't record the exact date) Howard Weaver was flying the university's Cessna 336 and crashed it  short of the runway at New Haven when both engines quit due to ice in the fuel system. The stories in the New Haven Register are pretty comprehensive, so I don't have to add anything here. Mr. Weaver obviously did a great job flying it to the ground. I have always felt that if a light plane is under control and at minimum airspeed you will very likely survive a forced landing. I spent one summer flying fire patrol in a 182 over the Bob Marshall Wilderness in Montana. I had dozens of spots picked out where I thought I could put the plane down and walk away. Of course the plane would have to be slung out by a helicopter and delivered to the recycler. I have owned almost 20 aircraft over the years, and I know some folks name their planes and get emotionally attached to them. I don't. Planes are expendable.

short of the runway at New Haven when both engines quit due to ice in the fuel system. The stories in the New Haven Register are pretty comprehensive, so I don't have to add anything here. Mr. Weaver obviously did a great job flying it to the ground. I have always felt that if a light plane is under control and at minimum airspeed you will very likely survive a forced landing. I spent one summer flying fire patrol in a 182 over the Bob Marshall Wilderness in Montana. I had dozens of spots picked out where I thought I could put the plane down and walk away. Of course the plane would have to be slung out by a helicopter and delivered to the recycler. I have owned almost 20 aircraft over the years, and I know some folks name their planes and get emotionally attached to them. I don't. Planes are expendable.

I had an incident similar to Mr. Weaver's in October 1976 when I was happily flying westbound in a Turbo 210 over North Dakota. I had just cleared an undercast when the engine quit cold, but kept windmilling. I fiddled with a few things, but Minot was right under me, so I concentrated on the deadstick landing, which was successful. We towed the plane to the maintenance hangar, found nothing wrong with it, and a couple of hours later continued the flight.

Very incidentally, Warren and Kent Pietsch have an FBO at Minot and fly airshows all over the U.S. Kent has "Jelly Belly" Interstates on both ends of the country and flies a heavy schedule. I have seen all the jet teams and most of the well-known acts, but Kent is far and away the best aviator of the bunch. The precision of his deadstick performance is awesome! Don't miss it! [ed note: see uTube video of his show here]

CHAPTER 11

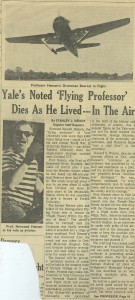

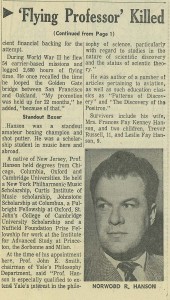

In James Gilbert's article in the March, 1966, issue of Flying magazine, Professor Norwood Russell Hanson is quoted as  saying, "Life is short. This has been almost a controlling feature in my life. For one thing my entire family is short-lived - I mean they just don't last very long." And later, "If the days are numbered and then it'll all be quite over, quite soon, one's inclined not to waste any time with ballet steps and with false noses."

saying, "Life is short. This has been almost a controlling feature in my life. For one thing my entire family is short-lived - I mean they just don't last very long." And later, "If the days are numbered and then it'll all be quite over, quite soon, one's inclined not to waste any time with ballet steps and with false noses."

Very sadly, Professor Hanson's self-prophecy came true on April 18, 1967, when the professor's Bearcat slammed into a hill near Ithaca, New York. He was on his way to Cornell to deliver a lecture titled "Flight Theory Within the History of Ideas." Before the flight Hanson had told me that there were some aeronautics students at Cornell who wanted to see his airplane up close. (He also told me some time earlier that he was going to write a book titled "Aristotle and the Principles of Aerodynamics." While us mortals would be full of skepticism, I knew that Russ's fertile mind saw a multitude of connections between Aristotle and aerodynamics.)

The weather was an issue. Nobody has ever asked me, but I surmise that Professor Hanson arrived in the area of Ithaca on top of scattered to broken clouds and was looking for a landmark to guide him down. This is the Finger Lakes area of western New York state. Seneca and Cayuga Lakes are fairly large; Owasco and Skaneateles Lakes are much smaller. Professor Hanson may have mistaken one of the smaller lakes for Cayuga Lake and made his penetration through the clouds toward terrain that was several hundred feet higher than around Ithaca. According to his mechanics  (from Asbury Park, New Jersey) who attended the memorial service at Pierson College a few days later, the canopy was open. The only salvageable part of the airplane was one wheel.

(from Asbury Park, New Jersey) who attended the memorial service at Pierson College a few days later, the canopy was open. The only salvageable part of the airplane was one wheel.

When the webmaster catches up, you must go back to Chapter Five and read James Gilbert's article, "The Bearcat Professor." The author captures the inevitability of this tragedy. Although I have described Professor Hanson as humble, he also had the swashbuckling bravado and arrogance our nation needs in a frontline warrior. Of course, he was way more than this. Truly a Renaissance man who excelled in his intellectual pursuits, the arts, and mastery of the physical world: aviation.

It's ironic that if not for the aeronautics students at Cornell, Professor Hanson probably would have been flying my Comanche 180. He went out on lecture tours several times, and I'd find a check with a neatly written itinerary taped to the control wheel. All the IFR enroute charts were on the back seat, and it wouldn't have been unusual to ask the controller for the approach procedure.

Professor Hanson has been gone 48 years now. He was a philosopher; I am not. He was a Type A person; I am not. When I was a student, he was the only professor I ever actually talked to. When I think of him looping the Golden Gate Bridge - well, there are a couple of bridges in Idaho, and I've often thought about flying under them....

CHAPTER 12

I hope someone out there is actually reading this; so far, zero feedback from eleven chapters. I, however, have truly enjoyed doing this. The history of aviation at Yale now goes back 100 years, and I felt compelled to share my recollections and aeronautica of fifty years ago: a few highlights (and lowlights) and observations that have shaped my aviation life in the past fifty years. They are in no particular order.

• I flew Slim the horseshoer from Spotted Bear to Schafer Meadow in a 182. I also had a huge bottle of propane on board. Slim had a cigar in his mouth, and I told him he couldn’t light it. Fifteen minutes later he had eaten it!

• Grass runways cover up all kinds of sins.

• If you want to go fast and inexpensively, buy or build an RV-8.

• Found myself on downwind in a Starduster Too biplane – inverted! I had been demonstrating basic aerobatics to my friend who had built the airplane. I reached out with both hands, gripped the stick with all my strength, and rolled the plane upright. There was no resistance. We had been flying for five or ten minutes with neither of us on the controls. I thought the maneuvers were a little sloppy, but not all that bad for a beginner. My knees were so weak I sat against the hangar for 30 minutes.

• My friends on the eastern plains of Montana say the mountains block their view. Normally we can see 40-50 miles; on a good day 100 or more. The curvature of the earth is an issue.

• You don’t need a Lexus to drive to the airport. You could have spent that bling on another glass gizmo and fuel for a year or more. I have a good friend who is a captain for Delta. His airport car is a clapped-out, rusty Subaru. Perfect!

• Good aviation writers are few and far between. Here are the best five:

Antoine de Saint-Exupery – “Wind, Sand, and Stars”

Beryl Markham – “West with the Night”

Ernest Gann – “Fate is the Hunter”

Charles Lindbergh – “We”

Richard Bach – “Jonathan Livingston Seagull”

• The best contemporary writer – Lane Wallace. (I am biased because I was mentioned in a “Flying” column in 2004.)

• Don’t invest in aviation.

• I have had a piece of the “Hindenburg” in my hand!

• Don’t ever buy an airplane that’s been near salt water. My brother had a Mooney based at Groton, CT. The flap tracks corroded off, the cylinder fins corroded off, and an impact screwdriver had to be used to loosen the cowl fasteners.

• Stirred up some dirt with the prop of my 210 at an airshow in Idaho. First person on the scene was a man who had “FAA” on his ball cap. “What are you going to do now?” he asked. I looked the prop over carefully; all three tips were curled over evenly. “Fly it home,” I said. “Well, you’re going to need a Special Airworthiness Certificate.” Which he filled out and gave to me. (But don’t think for a moment that there are sensible, old-school, experienced FAA inspectors still around.)

• I took off from Spotted Bear in a 182 one morning and found myself climbing toward the overcast at 140 mph with the power at idle. I cancelled flight ops for the rest of the day.

• Same airport, same airplane. Flew the last quarter-mile of the approach at full throttle all the way to the ground.

• Topped  the tank of my clipped-wing Cub at Caldwell-Wright airport for $1.29. Used a credit card to conserve my cash!

the tank of my clipped-wing Cub at Caldwell-Wright airport for $1.29. Used a credit card to conserve my cash!

• Flew my 1928 Travel Air 6000 from Minot, ND, to Wahpeton, ND, with a 60-knot tailwind. It was blowing 40 knots across the runway, so I landed on the grass  between the taxiway and the runway, into the wind. (The main wheels of the Travel Air are nearly three feet in diameter.) Rolled less than 200 feet. Taxiing to the ramp was the hardest part of the flight. [Editor’s note via Hank: Delta Air Service bought three of these in 1929 and started passenger service. (Delta had been in business for a few years dusting crops.) This airplane has six wicker seats, six windows that roll down, and a bathroom (with running water for the sink) in the back. The radial engine is a Wright R-975, 440 hp. It took Hank ten years to restore this plane. Eighty-five percent of the airframe (the tubular framework) is original; everything else is new. He has flown it about 900 hours all over the country in the last eleven years.]

between the taxiway and the runway, into the wind. (The main wheels of the Travel Air are nearly three feet in diameter.) Rolled less than 200 feet. Taxiing to the ramp was the hardest part of the flight. [Editor’s note via Hank: Delta Air Service bought three of these in 1929 and started passenger service. (Delta had been in business for a few years dusting crops.) This airplane has six wicker seats, six windows that roll down, and a bathroom (with running water for the sink) in the back. The radial engine is a Wright R-975, 440 hp. It took Hank ten years to restore this plane. Eighty-five percent of the airframe (the tubular framework) is original; everything else is new. He has flown it about 900 hours all over the country in the last eleven years.]

• Flying my Cessna Turbo 210 from Kalispell, MT, to Tucson, AZ, one winter morning, I watched the DME scroll past 320 knots while we were in the vicinity of Salmon and Challis, ID. We were on an instrument flight plan in severe clear at 15,000 feet. It was eerily smooth, and I had to continually trim as the ground speed slowly increased and then slowly decreased. I grabbed a sectional chart and confirmed that we were going six miles a minute.

• Then there was the time in North Dakota when we raced a UPS truck at 60 mph.

• Taxied my Pitts Special off a bridge . There was a dogleg in the taxiway, and I had my head down…. Never did find the propeller blades; fortunately they were made of wood. I still have the hub as a souvenir; well, actually more of a reminder.

. There was a dogleg in the taxiway, and I had my head down…. Never did find the propeller blades; fortunately they were made of wood. I still have the hub as a souvenir; well, actually more of a reminder.

• Took my instrument check ride in Missoula, Montana with Jack Hughes, chief pilot of the legendary Johnson Flying Service. The tower tried to give me my clearance as I was taxiing out. I refused. I looked at the inspector, and he had the hint of a grin. I knew at that moment, barring an egregious failure to fly half decently, I had already passed the check ride.

• My homebuilt Bucker Jungmeister biplane is in the final few months of construction. (When I was an undergraduate at Yale I could hand draw a Jungmeister, so now my aviation life is coming full circle.) It’s going to have the latest in glass; virtual vision, traffic, weather, and a host of engine monitors. I remind myself daily that the pilot has to keep his head up and not fall prey to the bug-eyed mastery of a gazillion gadgets. (I think I cribbed that phrase from Professor Hanson.) [Editor’s note via Hank: Before WWII the Germans developed their Bucker Jungmann two-place bipla ne trainer into a single-place stunt plane for the 1936 Olympics when aerobatics was an Olympic event. The fuselage and wings were shortened, and the horsepower was doubled. Hank’s airplane has a 180hp Lycoming engine inside a round cowling. Other than having a modern engine (and a glass cockpit!), this plane is an exact replica. A major feature is the pilot's seat which can be raised or lowered in flight. The controls are exquisitely balanced and dynamically neutral. (Hank has flown an original, and if you move the stick into a corner and then let go, the plane will continue to do what you commanded until it crashes into the ground!). He is hoping to have an empty weight of 950 pounds which will put it in the LSA category.]

ne trainer into a single-place stunt plane for the 1936 Olympics when aerobatics was an Olympic event. The fuselage and wings were shortened, and the horsepower was doubled. Hank’s airplane has a 180hp Lycoming engine inside a round cowling. Other than having a modern engine (and a glass cockpit!), this plane is an exact replica. A major feature is the pilot's seat which can be raised or lowered in flight. The controls are exquisitely balanced and dynamically neutral. (Hank has flown an original, and if you move the stick into a corner and then let go, the plane will continue to do what you commanded until it crashes into the ground!). He is hoping to have an empty weight of 950 pounds which will put it in the LSA category.]

• The Travel Air, on the other end of the spectrum, has a clock dead-center in front of the pilot. Watch it, and you won’t run out of gas. The other rudimentary instruments are obscured by the control column.

If you’re still with me, I hope you have enjoyed my scribblings over the past twelve months. Aviation has been my vocation at times, but always my avocation, and I hope you have, or will, enjoy it as much as I have. Adventure doesn’t just happen to people anymore; you have to go out and create it. My email address is: travelair@centurytel.net Come fly with me!